This work is an exploration and intensification of the question of the refugee and homeless children.

Open spaces, white or golden spaces intensely raising the question of being without a place or homeland or a house.

To be a homeless or a refugee for political or economic conditions imposed by war or life.

To be a material to media reports topping television or newspapers and interfaces

To be in an alternative fragile place and to live the idea of the temporary from generation to generation.

To be an object and the object is the alternative to your humanity.

Here and there are homeless children lost in the whiteness of nowhere.

Gold

Susanne Slavick is a professor at Carnegie Mellon School of Art in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Gold is precious. So is life – or so we assume.

But what can we assume in Bashar Alhroub’s Nowhere Project?

Gold is a constant in each image, invoking the alchemical pursuit. Physically and symbolically, transmutation and transformation are at the heart of the alchemical tradition -- whether pursuing the philosopher’s stone, the development of noble metals, or the elixir of life. A mixture of protoscience and mysticism, alchemy has become a metaphor for the creative act. Its practitioners sought to transform base metals into those of value – silver and gold. Artists also seek and enact transformation – of material, ideas and relations. Alhroub wrestles with the limits of this power.

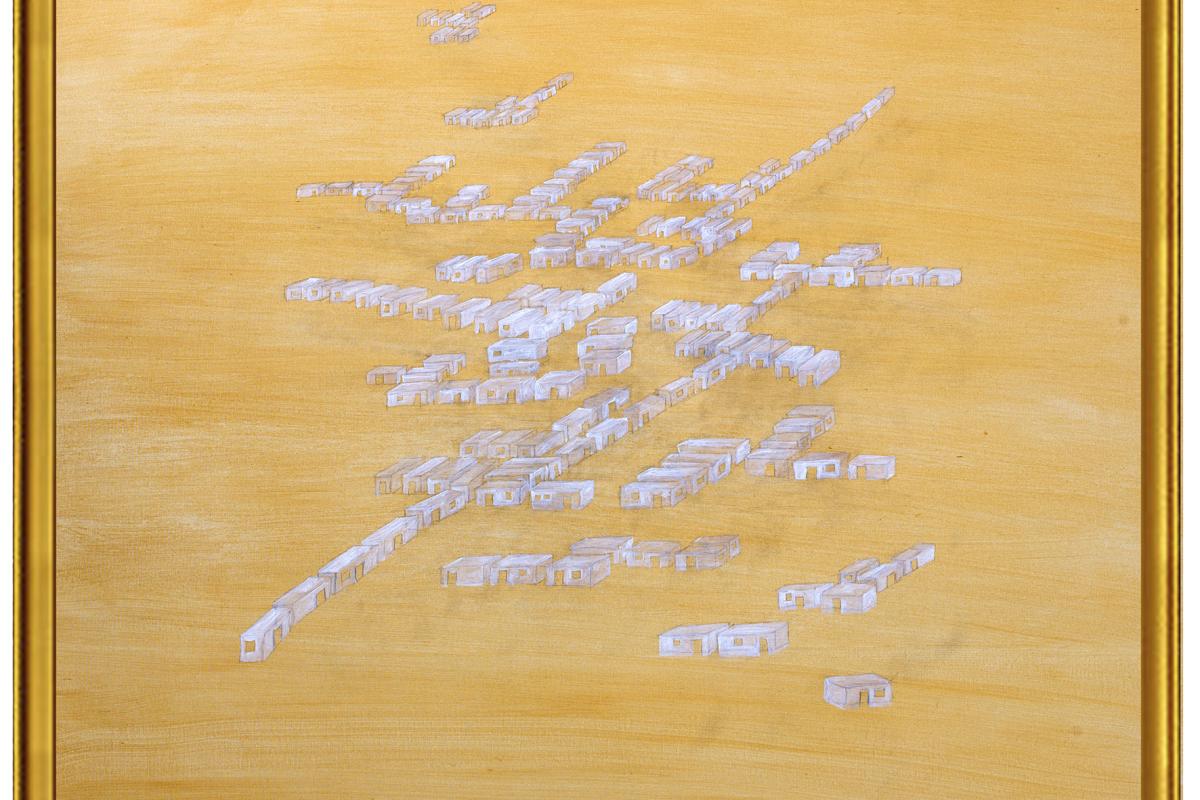

In Nowhere, simple white structures form constellations or float alone in fields of gold. The structures are temporary, uprooted, not grounded. And yet they are “home” – the only home available to countless refugees, proliferating for decades and currently at horrific speed under unspeakable conditions for occupied and exiled Palestinians. The omnipresence of gold may insist on value – that the lives conducted within these abodes are worth living and that they deserve more.

In other works, gold pronounces against other blank fields, isolating small pleasures and daily realities of the displaced. A child balances on a makeshift swing supported by two gold dumpsters. A child wearing gold sandals sleeps on a pillow of gold bricks; another shelters or slumbers in a carton. A boy helmets his head with a golf cardboard box. One bathes in a gold plastic tub provided by the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). A golden donkey bears children with their bundles wrapped in gold; unaccompanied children stand cloaked in a blanket or proceed with their meager belongings, each delineated in gold. Common discarded objects become comforts, shelters, and playthings in dire circumstances; necessity becomes the mother of invention.

Alhroub’s assignment of gold to each object and to the entirety of place struggles to confer and maintain value. It is a Sisyphean struggle as the gold is artificial. It has no real luster, applied in streaky acrylic washes. Its fakeness washes over each scene and stresses each detail, embodying falseness of a greater order. Is this gold “fool’s gold,” representing the hypocrisy of nations and peoples who proclaim respect for human lives and advocate, then abrogate, human rights?

Two images return us to “nowhere”. One shows three children with smiling faces birthed into nowhere, flashing “V’s” for peace or victory with their small fingers. The last image in the series shows a lone boy. One hand points a golden toy gun toward the sky; the other clutches two suction-cupped darts. Their tips are blood red. What futures await for over seven million displaced Palestinians, 6.6 million of whom are refugees with nearly another half million internally displaced? What will victory mean and how will peace be won?

Gold might represent stability in that it is one of the least reactive chemical elements and is non-corrosive. It may gleam in the most inhumane conditions, but for how long? In Nowhere, its glimmer is alluring, but ultimately anemic—converted to cheap plastic, barren land, and empty sky. It is a veneer over the untenable. Nowhere must become somewhere.

Susanne Slavick, August 5, 2014

Nowhere

Andrew Ellis Johnson

The source imagery for Bashar Alhroub’s “Nowhere” project, that of children in UNCHR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) camps, is familiar and ubiquitous. Out of expediency, necessity and economic design, these camps assume generic appearances; their locales are nebulous. They are not meant to exist in our world.

Images of refugee camps are mediated and de-contextualized. The content is generalized and seemingly benign; its portrayal of children is sentimental. The purposes for its publication are diverse and manipulated, typically making personal appeals that mask systemic violence of which the viewer remains ignorant and often culpable.

Refugee children from Afghanistan, Cambodia, Gaza, Haiti, Iran, Iraq, Kenya, Laos, Lebanon, Liberia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Somalia, South Sudan, Syria, Vietnam, and Ukraine, among others are quarantined in camps, some having been born there, and their plight promoted. In the West the media conflates distinct refugee populations and the camps they live in, downplaying the specific political conditions that created them. There are ideological advantages for maintaining “Nowhere”; the specific politics of place get too messy. Such ploys pay; they do not condemn.

No one is particularly responsible for ‘no where’. Children are certainly not; they have no say in being ‘no where’. The children of “nowhere” mime and pose for the camera with universal gestures, like any other children. Their images are staged if candid, their activities constructed if innocent, their needs framed if urgent and pleas controlled if common. They present themselves to us without reproach. We are free to sympathize, contribute, donate, support, and better assist them to ‘heal and play’ through our generosity and purchases. To assist them neither erases our complicity nor strikes us as hypocritical. Our consciences remain intact and unperturbed, as intended.

Bashar Alhroub forces us to focus on the problems inherent in undifferentiated appeals to sentiment by furthering the isolation of his figures. His execution is crude, his compositions calculated. Stripped of photographic detail, his painted spaces are flattened and his figures all but voids. The untouched paper or initial imprimature swallow his figures, which are dwarfed if whole, fragmented if occluded. One boy is crushed, flattened by the cardboard box he is in. He could never emerge from this hiding place, tunnel or grave.

Alhroub frustrates any attempt at identification with the figures who are roughly sketched, unfinished, and painfully so. Unlike a sign or symbol, these figures prefigure rather than stand in for personages. They seek to emerge but remain undeveloped. Far from seeing into the psyche of an individual, his figures are without personality. Many of them are stuck together in a naked solid block or are sandwiched between shapes as with the boy swinging on a chain between dumpsters or another flanked by a brick and a heavy sandal.

The strength in Alhroub’s “Nowhere Project” is in what it precludes us from seeing or knowing. The constant media appeals that hover between the cute and bathetic often appeal to our ‘paternalistic’ instincts to aid or rescue the ‘undeveloped’ and ‘unfortunate’. Through what it withholds, the “Nowhere Project” makes clear how frequently we are requested to respond without questioning, act without thinking, contribute without acknowledging our own participation in creating the very circumstances we are asked to alleviate.

Alhroub’s images are extracted from ongoing crises, undeniable catastrophes and inexcusable suffering—real circumstances that must be addressed in their particularities. Each is separable even if parallels exist; their causes are discernable and remedies achievable. This ubiquitous ‘Nowhere’ in fact exists nowhere. The media’s conflation of multiple no man’s lands does not make them a single lot. They must be distinguished from one another before there can be any relief from the full extent of their own particular horrors.

In Gaza, massacres by Israel, facilitated by the USA, are taking place again as I write and the world watches. Occupied Palestine will soon be presented as yet another humanitarian crisis with endless photo opportunities in a ‘Nowhere’. But the dead, wounded and displaced are never photogenic or telegenic in real life. Atrocities cannot be retouched nor war crimes whitewashed. We must stop perpetuating and committing them.

Andrew Ellis Johnson

August 5, 2014